Lipoprotein(a): A Lifelong Marker for Cardiovascular Risk and Prevention

- Dr Andes

- Dec 28, 2025

- 5 min read

Lipoprotein(a), usually shortened to Lp(a), is a genetically determined cholesterol-containing particle that accelerates vascular ageing and raises the lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease, making it a key marker in longevity medicine.¹⁻² Understanding your Lp(a) level helps refine long-term risk estimates and guides how aggressively to protect your heart, brain and arteries.³

What is Lp(a)

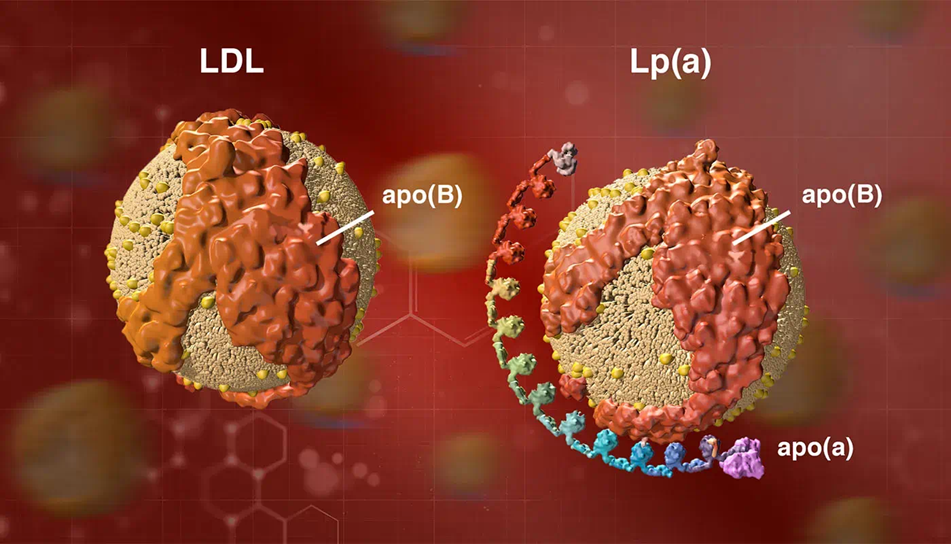

Lp(a) is a lipoprotein particle that looks similar to low-density lipoprotein but has an extra protein called apolipoprotein(a) attached to apolipoprotein B.¹ This structure makes Lp(a) both atherogenic and prothrombotic because it carries oxidised phospholipids and interferes with normal clot breakdown.¹⁻⁴

Levels of Lp(a) are set mainly by your genes and change little with age or lifestyle, in contrast to standard cholesterol.¹⁻⁵ About one in five people worldwide have significantly raised Lp(a), which is enough to meaningfully increase cardiovascular risk.²⁻⁶

Why Lp(a) matters

Large genetic and observational studies show that higher Lp(a) is causally linked to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and calcific aortic valve stenosis.⁴⁻⁷ People in the highest third of Lp(a) values have roughly seventy per cent higher risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular events than those in the lowest third.⁸

Raised Lp(a) is also associated with coronary plaque progression and with higher mortality in people with ischaemic heart disease.⁵⁻⁹ Over decades, this translates into more heart attacks, strokes and valve disease, which directly erode health span as well as lifespan.²⁻³

How to use an Lp(a) test

Modern consensus statements recommend at least one Lp(a) measurement in every adult as part of personalised cardiovascular risk assessment.⁷⁻¹⁰ Because Lp(a) is mainly genetically fixed, a single result usually remains valid for life unless there is major illness such as advanced kidney disease.¹⁻³

Commonly used bands are:

Low risk: below about 75 nanomoles per litre

Clearly elevated: at or above about 125 nanomoles per litre, where Lp(a) is considered a risk-enhancing factor.⁷⁻¹⁰

In longevity-focused care, a high Lp(a) result supports:

tighter low-density lipoprotein cholesterol targets

earlier use of potent lipid-lowering therapy

more intensive lifestyle optimisation and monitoring, for example through coronary calcium scoring or vascular imaging in selected individuals.³⁻¹¹

Managing elevated Lp(a) today

There is currently no widely available therapy that exclusively targets Lp(a) with proven outcome benefit, so management focuses on reducing overall cardiovascular risk while research on specific drugs continues.¹⁻²

Lifestyle approaches

Eat a cardioprotective pattern rich in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, pulses, nuts and fish while limiting saturated fat and avoiding trans fats, which improves global cardiovascular risk even though Lp(a) itself changes little.¹²⁻¹³

Maintain regular physical activity and healthy body composition, which lowers blood pressure, improves insulin sensitivity and reduces overall event rates in people with raised Lp(a).³⁻¹¹

Do not smoke and minimise exposure to second-hand smoke because tobacco use adds substantially to the prothrombotic and inflammatory effects of Lp(a).⁴⁻¹⁴

Medical strategies

Lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol as much as possible using statins, ezetimibe and, when needed, PCSK9-targeted therapies, because reducing low-density lipoprotein cholesterol mitigates much of the absolute risk attributable to Lp(a).¹⁻³⁻¹¹

PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies and inclisiran reduce Lp(a) by about twenty to twenty-five per cent in addition to strong low-density lipoprotein cholesterol lowering, although they are not approved specifically as Lp(a) drugs.¹⁻²⁻¹⁴

Lipoprotein apheresis, a procedure that filters lipoproteins from the blood, can reduce Lp(a) levels by around sixty per cent and is used in selected very high-risk patients with progressive disease despite optimal medical therapy.⁷⁻¹⁵

Older agents such as niacin can lower Lp(a) but have not shown cardiovascular benefit in modern trials and are not recommended solely for this purpose.¹⁻²

Emerging Lp(a)-targeted therapies

Several RNA-based medicines that act directly on the LPA gene are in advanced clinical development and are often described as potential blockbuster drugs.¹⁻²⁻⁴

Pelacarsen is an antisense oligonucleotide that reduces apolipoprotein(a) production and has lowered Lp(a) by about eighty per cent in phase two trials.¹⁻² A large phase three outcomes study called Lp(a)HORIZON is testing whether this reduction prevents cardiovascular events in patients with established disease and high Lp(a).¹⁻¹⁶

Olpasiran and other small interfering RNA agents such as zerlasiran and lepodisiran have shown reductions of roughly sixty to ninety per cent in Lp(a) with infrequent dosing, and phase three outcome trials are underway or planned.²⁻⁴⁻¹⁷ If these studies confirm safety and benefit, they are likely to change how clinicians manage genetically high Lp(a) in both secondary and, in time, high-risk primary prevention.¹⁻²

From a longevity perspective, measuring Lp(a) once, acting decisively on all modifiable risk factors when it is elevated and staying informed about emerging targeted therapies provides a pragmatic framework to protect cardiovascular health across the lifespan.³⁻¹¹

References

Manzato, M. et al. Lipoprotein (a): underrecognized risk with a promising future. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 25, 393 (2024). https://doi.org/10.31083/j.rcm2511393

Tsimikas S. Lipoprotein(a) in the year 2024: a look back and a look ahead. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 44, 1027–1041 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.124.319483

Parcha V, Bittner V. A. Lipoprotein(a) in primary cardiovascular disease prevention is actionable today. Am. Heart J. Plus 57, 100581 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahjo.2025.100581

Greco A, Kallikourdis M, Tsimikas S, et al. Lipoprotein(a) as a pharmacological target: premises, promises, and prospects. Circulation 151, 400–415 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.124.069210

Puri R, Ballantyne CM, Hoogeveen RC, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and long-term plaque progression, low-density plaque, and pericoronary inflammation. JAMA Cardiol 9, 939–949 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2024.1874

Bhatia H.S. Lipoprotein(a) at a “tipping point”: case to move to universal screening. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 23, 101274 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpc.2025.101274

Kronenberg F, Mora S, Stroes ESG, et al. Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic valve stenosis: a European Atherosclerosis Society consensus statement. Eur Heart J 43, 3925–3946 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac361

Reiss A.B., Gulkarov S., Pinkhasov A., De Leon J. & Ossowski V. Role of lipoprotein(a) reduction in cardiovascular disease. J. Clin. Med. 13, 6311 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13216311

Loh WJ, Koh XH, Yeo C, et al. Lipoprotein(a) as a predictor of mortality in hospitalised patients with ischaemic heart disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 16, 1541712 (2025). https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2025.1541712

Kronenberg F. Frequent questions and responses on the 2022 lipoprotein(a) consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Atherosclerosis 373, 1–10 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2023.05.002

Ao L., van Dijk K.W., Burgess S., et al. The interactions of lipoprotein(a) with common cardiovascular risk factors in cardiovascular disease risk: evidence based on the UK Biobank. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 22, 101008 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpc.2025.101008

Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Vadiveloo M, et al. 2021 dietary guidance to improve cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 144, e472–e487 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001031

Bhatia, H. S., Hurst, S., Desai, P., Zhu, W. & Yeang, C. Lipoprotein(a) testing trends in a large academic health system in the United States. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12, e031255 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.123.031255

Ao L., Noordam R., van Dijk K. W., et al. The interactions of lipoprotein(a) with common cardiovascular risk factors in cardiovascular disease risk: evidence based on the UK Biobank. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 22, 101008 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpc.2025.101008

Gianos E, Duell PB, Toth PP, Thompson GR, et al. Lipoprotein apheresis: utility, outcomes, and implementation in clinical practice: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 44, e00–e00 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1161/ATV.0000000000000177

Cho L, Nicholls SJ, Nordestgaard BG, Landmesser U, Tsimikas S, Blaha MJ, et al. Design and rationale of Lp(a)HORIZON trial: assessing the effect of lipoprotein(a) lowering with pelacarsen on major cardiovascular events in patients with CVD and elevated Lp(a). Am Heart J 287, 1–9 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2025.03.019

Sosnowska B, Surma S, Czupryniak L, Romuk E, Jozwiak J, Banach M. 2024: The year in cardiovascular disease – the year of lipoprotein(a). Research advances and new findings. Arch Med Sci 2, 353–368 (2025). https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms/202213

Comments